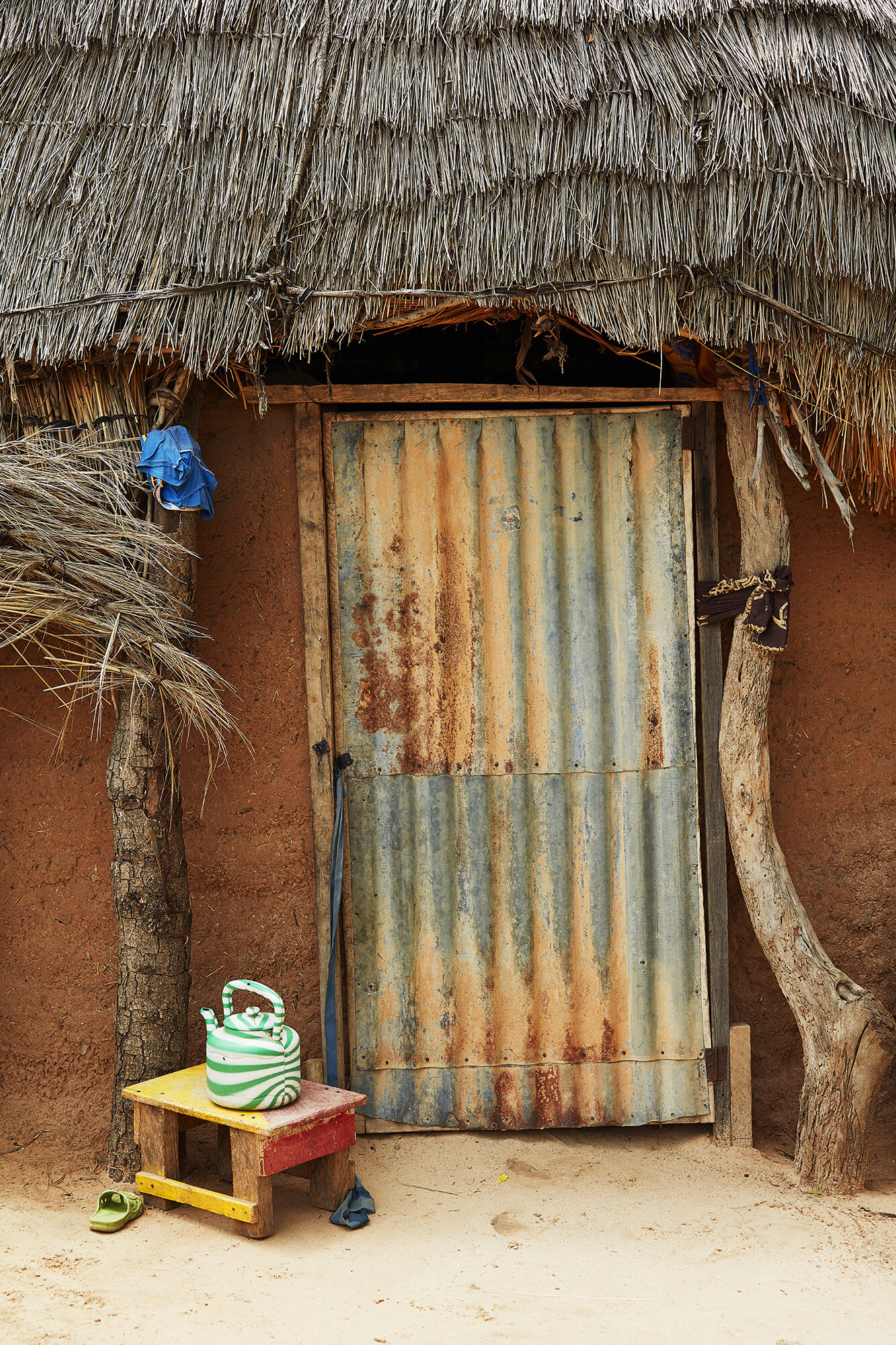

Niger

Photography by Yuki Sugiura

Commissioned by Kimberly Hoang for The British Red Cross

Words by Imogen Lepere

Although I would have loved to interview her in person, I meet Yuki Sugiura via Zoom due to lockdown travel restrictions. The lighting is subtle in her Peckham studio and she’s leaning against a white brick wall, sipping Chinese tea from a ceramic cup. Not a hair of her pixie cut is out of place. In fact, she’s as serene and understated as one of her mesmerising portraits.

Sugiura is a London-based lifestyle photographer whose work has adorned the pages of some of the world’s best known titles, including Condé Nast Traveller US, Monocle and The New York Times. Although her primary subject is food, what she’s really interested in are the stories of the people who interact with it. “As a child growing up in Tokyo, family meals were sacred. My mother treated them almost like religious rituals. French pastries, Russian dumplings and Chinese stir fries – she travelled around the world through cooking.”

“It was a tough shoot as I didn’t want the locals to feel like they were being taken advantage of or fetishized,” Sugiura reflects.

When The British Red Cross approached her to cover the chronic food shortage in Niger, Africa, for a new campaign she leapt at the chance, although knew it would be a challenge. The semi-arid Sahel region drags its dusty tongue all the way from Senegal to Sudan and has one of the driest climates on the planet. Its seven million residents live in extreme poverty, including 1.5 million children who are classified as acutely malnourished by UNICEF. However, due to global warming, scientists are predicting that temperatures could rise several more degrees by the end of the century. For the vulnerable communities who call Niger home, survival would be impossible.

“It was a tough shoot as I didn’t want the locals to feel like they were being taken advantage of or fetishized,” Sugiura reflects. “Coming from a place of immense privilege is something I really struggle with when working with impoverished communities, so I knew I couldn’t just wander around snapping, reportage style.”

For portraits, she made a point of creating a pop-up studio, no easy matter in rural sub-Saharan Africa. “I hoped that extracting the person from their everyday situation and inviting them to have a proper portrait session would afford them more dignity than just capturing them and moving on.” Her subject helped to choose the location and she used a portable background, which she believes helped make the portraits look like a cohesive series. The resulting images are all the more moving for their subtlety. A mother stares stoically into the camera as her children’s hands pluck beseechingly at her dress. An elderly man is spick and span in a sky-blue uniform with a colourful hat. Only the shadows on either side of his clavicle and the litter scattered across the scrubby ground behind him hint that something might be amiss.

The food itself also presented a challenge. The most common dish is ‘tuwo’, a thick white paste of drought-resistant millet which has little nutritional value. “Sadly, many of the adults didn’t eat at all during the day and instead gave up their share for the children. Despite the fact the kids were hungry, they were super respectful of each other, waiting patiently until their turn came and helping to feed the younger ones. I tried to capture the beauty of this sense of community, while also depicting the want in their eyes.”

Whether in Japan or Niger, it seems that sharing meals with loved ones is an essential thread in the fabric of life.

Since it gained independence from France in 1960, Niger has been afflicted by political unrest causing untold suffering for civilians – and also logistical issues for the team. “Although we were there for a week, we could only leave our hotel at certain times because of security and we had to cover a lot of ground on uneven roads. I only had about 14 hours of actual shooting time, all during the brightest part of the day.” Personally, I think the dazzling light works as a metaphor for the harshness of life in Niger.

“I shot on a Canon 5D and tweaked the colour contrast to make it a little more vibrant, but don’t ever do much post production. I like my work to be authentic, to show the intrigue in something as it actually is rather than constructing a look for the camera.”

So, would she do more of this kind of work despite its challenges? “Oh yes. When I was a little girl I wanted to be a war correspondent. Climate change is making it ever harder for vulnerable people like those in Niger to get by. In the west, our choices affect people who many of us don’t even know exist. I feel a moral obligation to witness their struggle and raise awareness.”

First though, she wants to go home to Japan to visit her family, who live on the coast an hour south of Tokyo. “When lockdown lifts, the thing I’m most looking forward to is spending hours eating fresh sashimi by the sea with my parents.” Whether in Japan or Niger, it seems that sharing meals with loved ones is an essential thread in the fabric of life.

How you can help

The British Red Cross coordinates the work of ten Red Cross and Red Crescent organisations across the Sahel region. They support The Niger Red Cross in providing life-saving cash grants to vulnerable people caught up in drought or other emergencies that result in food shortages. This much-needed money also helps to keep local markets functioning. If you’d like to help, donate to The British Red Cross disaster fund: donate.redcross.org.uk